Introduction

Since spring 2020, his name has been commonplace even to those beyond the realms of science and academia. German physician, epidemiologist and hygienist Robert Koch is seen as a pioneer of microbiology. The institute that bears his name is Germany’s collection point for and source of information, publishing daily updates on the number of cases and the latest insights throughout the coronavirus pandemic.

Could Robert Koch himself ever have imagined a pandemic like this one? Whatever the case, he would undoubtedly have worked just as tirelessly as the staff of the eponymous Robert Koch Institute (RKI) to study and combat it. The secret of his success was simple: “I never give up,” he said, commenting on winning the 1905 Nobel Prize for Medicine for his research into tuberculosis. To this day, his research back then has set the standard in the study of infectious diseases and hygiene. “You don’t have to know who discovered the tuberculosis bacillus,” he once modestly asserted. That said, besides being an inquisitive and tenacious fighter for his cause, Koch was also decidedly ambitious. Born on December 11, 1843, the third of 13 children of a mining official, Koch began collecting and cataloguing various plants even as a boy. After earning his Abitur (German high school degree) at the classical grammar school in his native Clausthal, he went on to study medicine in Göttingen. He worked as a hospital doctor in Hamburg, near Hanover and in Potsdam before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. He volunteered for service as a medical orderly and, at a field hospital, mainly treated soldiers suffering from dysentery and typhoid – both of which were serious bacterial diarrhoeal diseases, often with fatal outcomes. At the end of his military service, he completed his exams to become a public health officer at the municipal hospital in the province of Poznan in 1872. Alongside this ‘day job’, he also served as a court-certified expert and ran a private practice to treat the poor and needy.

1854: Robert Koch (top row, left next to the mother) with his family in Clausthal in the Harz region. Much earlier, at the age of five, he astounded his parents by teaching himself to read using the newspaper. Early indications of his perseverance and determination. © RKI

Logical structures and meticulous precision

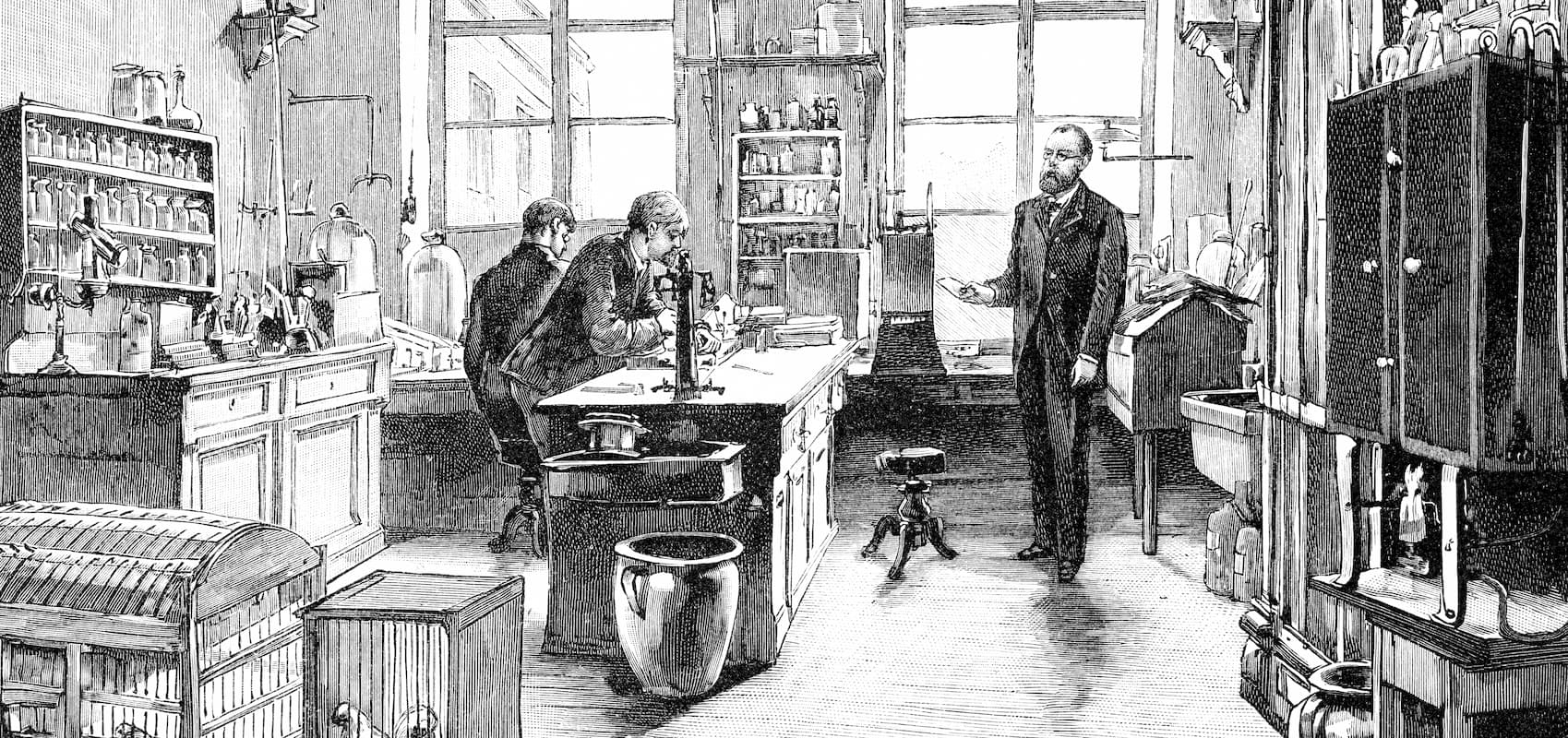

Despite so many practical demands on his time, Robert Koch maintained a keen interest in research, conducting experiments in the small, primitively equipped laboratory he had set up in the house where he lived. He was supported by his wife Emmy, a medical technical assistant. Consistently logical structures and meticulous precision were the hallmark of the couple’s experiments. And for good reason: At the time, the epizootic (animal) disease anthrax not only drove many a farmer in the region to rack and ruin, but repeatedly also afflicted humans. Koch identified rod-shaped entities in the animals’ blood as pathogens that form resilient spores. He successfully isolated them and proved his theory by using them to make healthy animals sick. Koch was a huge fan of microscopes made by Carl Zeiss, a pioneer in the optics industry. Once, when placing an order with Zeiss for a microphotographic device, he wrote: “I have succeeded in impregnating the bacteria with dyes that do not change their form and make them visible with exceptional clarity.” Koch became the first bacteriologist of his day to deduce why a pathogen can resist various environmental factors and what conditions must be met to cause an infection. His key insight? “The bacterium is nothing; the milieu is everything.” In other words, bacteria cannot affect a healthy immune system, but disease occurs when this system is weakened.

Robert Koch in 1896 on an expedition in Egypt with his second wife Hedwig. © Archiv der HU zu Berlin/RKI

Loading component...

In 1906, while searching for the causative agent of sleeping sickness, Koch (on the right) dissects a crocodile on the Sese Islands in Lake Victoria, Africa. © RKI

.jpg%3Fmw%3D1080&w=1920&q=75)